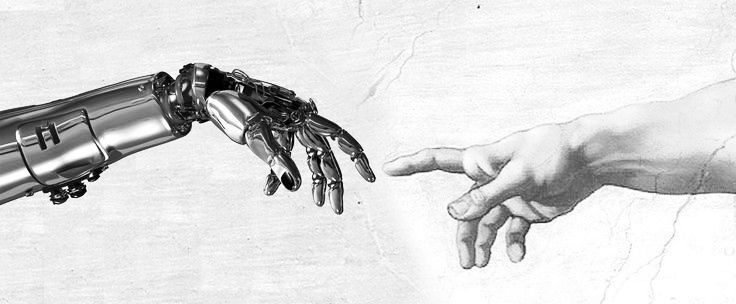

Are capital allocators deciding the future of AI?

Engineers won’t decide the future of AI. It will be decided by the massive wave of billionaires financing AI infrastructure. Increasingly, that money isn’t coming only from wealthy investors. It includes state pension plans and ordinary people’s retirement savings.

Consider Blue Owl Capital. In the middle of the AI bloom, it raised about $30 billion to build an AI data center for Meta in Louisiana, putting in $3 billion of its clients’ money and borrowing the rest. Blue Owl went from niche lender to a $259 billion power broker in a decade. Moves like this orchestrate the incentives in the AI race: the money isn’t theirs, but the decisions are. Those choices push the vast amounts of capital into AI infrastructure, consolidating a singular strategy: expand rapidly, scale relentlessly, then ruthlessly monetize hardware and the income it generates.

Quietly, a different concern is building: protection.

When AI policy ignores the financial inducements and only demands regulations on model behavior–“ethical” responses, risk management, kinder chatbots – it becomes a philosophical circus. We end up asking how polite AI engines should sound, rather than who is funding them and what returns they are structurally forced to chase. A strong, rigorous legal regime for AI has to look for a foundational base: in the capital frameworks that shape it, and in how their incentives can both accelerate innovation and amplify harm in an era of uncertainty sold as a golden ticket to progress.

To establish a foundational base for AI policy, we need to follow the money. AI infrastructure has become a financialized global product—an international asset funded by private credit, bond markets, and ultimately, average citizens’ savings. It is important to emphasize that most AI regulation only determines the conditions on model behaviour, not the capital architecture that makes those models possible. As a consequence, if we keep this disproportionate relationship, democratic institutions will end up bearing the risks of this AI bubble without ever having a say in how capital is deployed, due to the reality of invisible antitrust regimes or hands-off laws that create a series of extremely concentrated interests.

AI infrastructure as a financial product

The Hyperion data center in Louisiana is an illustrative example of this evolving context. Meta didn’t simply “build a data center.” It entered into a joint venture in which funds managed by Blue Owl Capital own about 80% of the project, while Meta retains only 20%. Around $27–30 billion is being raised through a mix of private debt and equity, organized by banks like Morgan Stanley and bought by asset managers such as Pimco and BlackRock. Hyperion is more than expected to deliver 2 gigawatts of compute power for training large language models—while keeping most of the financing off Meta’s balance sheet.

For the investors, this isn’t “AI ethics.” It’s yield. Pimco reportedly took around $18 billion of the Hyperion bonds and is already sitting on billions in paper profits. BlackRock’s ETFs bought over $3 billion, turning the project’s debt into mainstream investment vehicles. In other words, anyone holding a diversified bond ETF in their retirement account in the U.S could now be indirectly financing a single AI data center in rural Louisiana.

Hyperion is not an exception; it is the blueprint. Private credit funds and infrastructure investors are positioning data centers as a new asset class alongside toll roads and airports—fueled by their high-credit leases, recurring revenue, and formidable barriers to entry. This is no longer “tech real estate.” We are discussing state-scale technological powerhouses.

Other deals—like multi-billion-dollar AI campuses in Texas backed by firms such as Silver Lake and DigitalBridge—are subject to the same pattern: concentrated capital, long-lived assets, and a business model that depends on constant demand for AI compute. Analysts now estimate that Big Tech will need more than a trillion dollars in new capital to finance the AI boom. The race is no longer just about better algorithms; it is about who can turn AI infrastructure into the safest, most extensible financial product.

How do local pensions relate to democratic stakes?

Once you view AI infrastructure as a financial asset, a concerning question arises: whose money is actually at risk? An increasing share of the capital behind these mega-deals comes from state and local pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance portfolios. Analysts monitoring climate and infrastructure risk are already warning that data-center build-outs— in particular those driven by fossil-heavy grids—could evolve into a new systemic threat to public pensions. The same funds that pay teachers’ and public workers’ retirements are now partially exposed to the success or failure of hyperscale AI bets.

That is where the democratic problem begins. Pension trustees and retail investors rarely vote on whether billions of their savings should be used to finance concentrated AI infrastructure in specific regions. They see a fund label, not a hyperscaler’s data-center term sheet. Yet the capital they provide is what allows Big Tech to externalise risk: Meta gets compute capacity and strategic flexibility, while bondholders—and, by extension, pensioners—bear the downside if the economics of the AI race change. It is an individualistic fight for power, with citizens and ordinary people suffering the consequences, and it aims for the illusion of better opportunities in a system ruled by a small elite.

But isn’t this just rational investing?

Many supporters would emphasize that nothing here looks like a crisis. Pension funds require long-term, reliable returns. Data centers are a critical infrastructure. Off-balance sheet structures and special-purpose vehicles are standard practice in project finance. So in their telling, Hyperion is not a democratic matter; it is a responsible capital allocation that matches long-lived assets with long-lived capital. That is the logic many asset managers and pension trustees operate under. That logic shows how the same arrangement can be financially rational and democratically harmful, since it is a bet on ever-growing demand.

A new AI regime that allows transparency

It’s very easy to ignore AI policy, as we’ve seen in the United States—ironically, one of the fiercest competitors in the AI race. Washington now talks about AI in Manhattan Project terms. Figures like Jacob Helberg, a national-security strategist who has argued for a “techno-industrial mobilization,” helped push the idea that America needs a wartime-style effort to prevail over China in AI. The result is the federal AI initiative known as the Genesis Mission, officially launched in November 2025 and advertised as a historic national project.

But the instruments of this “national project” look very familiar: subsidies, tax credits, procurement, and deregulation that channel more public money and political legitimacy into the same small circle of hyperscalers and financiers. In rhetoric, Genesis is about democratic survival and technological sovereignty. In practice, it deepens dependence on a handful of private actors who own data centers, control chips, and intermediate capital. That is exactly the public–private split this essay is about.

When states frame AI as an existential race, they justify ever larger subsidies and security exemptions—but rarely demand commensurate governance of the capital structures behind those systems. Contemporary society evokes a classic analogy: as Juvenal once said, “Give them bread and circuses, and they will never rebel.” And that’s exactly why the public is mobilized in the name of ‘national AI,’ while the real power over chips, data centers, and debt remains firmly private.

The lack of coherence the US demonstrates in a desperate attempt to dominate this new digital regime is evident in its contradictory strategy, especially in industrial policy. The Chips Act is an example of this, giving tens of billions to the U.S chip manufacturing, which is at the same time threatened by the administration labeling it as “uncertain”. This produces a messy mix: claiming sovereignty, wanting to police AI globally, but paradoxically sabotaging its own institutions when meaningful AI rule-making happens less in legislatures and more in billionaire retreats and private finance clubs where they decide who will have access, which regions become AI hubs, who smaller labs have to rent from, and how dependent governments become on a few providers.

If we take it seriously, AI policy cannot remain a stage play while capital quietly locks in the real power structure. A capital-aware regime should start with basic transparency: when public pensions and retail funds back hyperscale data centers, beneficiaries should know where their money is going, what risks they are underwriting, and how concentrated those bets are. Regulators could require stress tests that include AI infrastructure exposure, just as banks are tested for housing or credit shocks. Securities and pension law should recognise hyperscale AI projects as systemically relevant infrastructure, not just another “alternatives” allocation buried in a portfolio line item.

Democratic institutions need an urgent voice that acts not only on the press but also in frameworks that provide the conditions under which public savings are used to finance private AI power. That does not mean micromanaging every data center. It means setting guardrails:

- Impose non-discriminatory access rules on GPU clouds and data-center operators, so they cannot quietly favor their own labs and starve innovators.

- The mission of law is to set standards in AI conduct, and that must be reflected in how lawyers scrutinize exclusive cloud and capital deals between platforms that command frontier AI labs as a de facto merger, to prevent an AI oligarchy.

- Make public subsidies for chips and AI infrastructure contingent on open access where possible, competition safeguards, and minimum safety investment—so we subsidize public policy, not private monopolies.

- Dedicate part of the returns obtained from large AI infrastructure and firms to fund independent evaluation institutions that tech giants do not control.

A few will decide the future of AI, and those few will determine where. The key point is that “where” is the quantitative amount of credit committees, asset managers, and a handful of hyperscalers spending other people’s savings, which are constantly compounding. If we want AI to have a disruptive and beneficial future for this generation and the next one, AI policy has to move upstream and meet capital where it lives. That means asking harder questions of pensions, regulators, and companies before the next trillion flows into concrete, chips, and debt. Otherwise, we are leaving the most consequential political choice of this decade—who controls our computational infrastructure—to people whose only legal obligation and mission is to make the numbers go up. These same people have no legal obligation to prioritize innovation, competition, or the rule of law—let alone social justice. They’re legally bound to make the numbers go up. That’s it.

So the question is not whether AI will transform society. It will. The question is: who decides how and where? Engineers, or the people financing them? Regulators, or credit committees? Democracy, or default? And remember to think critically about location since it is where power is.

Right now, we are not choosing; we are reacting to default. And that choice is being made in rooms most of us will never enter, with money most of us didn’t know we were lending.

Write to Casandra Moreno at casandra@thelawsofai.com

Leave a Reply